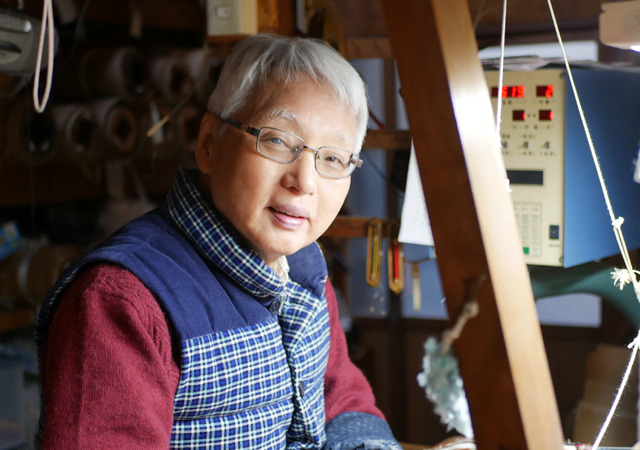

Okamoto Mie

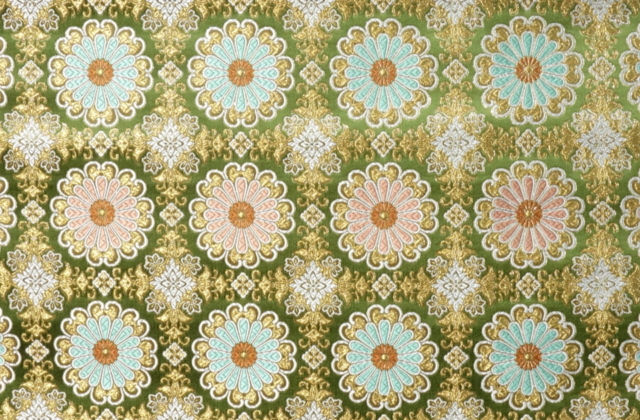

Wife of Tadao. Born in Nishijin to a obi weaver, she had been weaving obis after graduating from high school. She is the best in the company in handling silk, including inspecting and preparing threads.

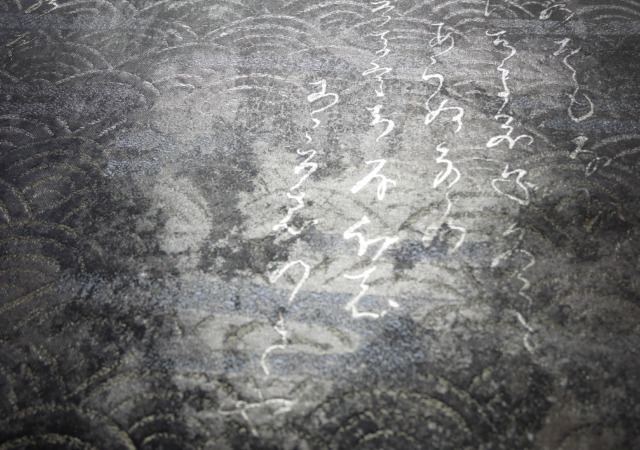

I was born and raised in an obi shop in Nishijin. Because we are one in the industry, I can see the work even if I don’t want to, and I can understand what they are doing. Sooner or later, I naturally began to be able to do more and more things, such as saying, “The yarn winder is stopped,” or “You should fix it. It became so familiar in my daily life that I cannot explain how to weave even if someone asks me how to weave again. I had been weaving at home for several years, so I brought a obi belt I had woven myself as a trousseau. I was a little nervous about marrying into this family and working with them in the family business, but I accepted it as a matter of course, even though I was a little nervous when I saw the looms with cloth widths wider than the obi.

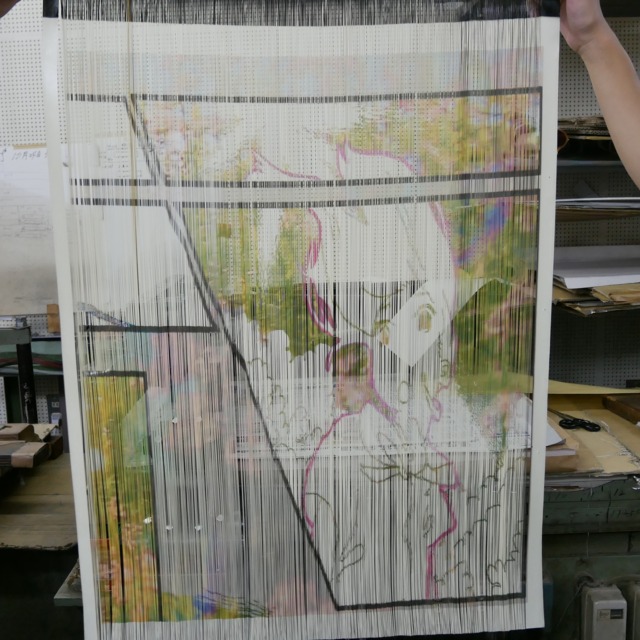

However, it was different from weaving obi on power looms, and I was nervous when I entered the factory where handlooms were lined up. However, I was relieved to find that I could make use of my experience in handling threads. The trouble is that the warp threads sometimes break all at once, and I am at a loss as to what to do in such cases. But if I take my time and reinsert the warp threads one by one, I am sure I will be able to manage. I never feel like throwing it out. I think it is natural for me to be in contact with threads and fabrics. As I get older, it gets harder to see the details, but I can still see the threads.

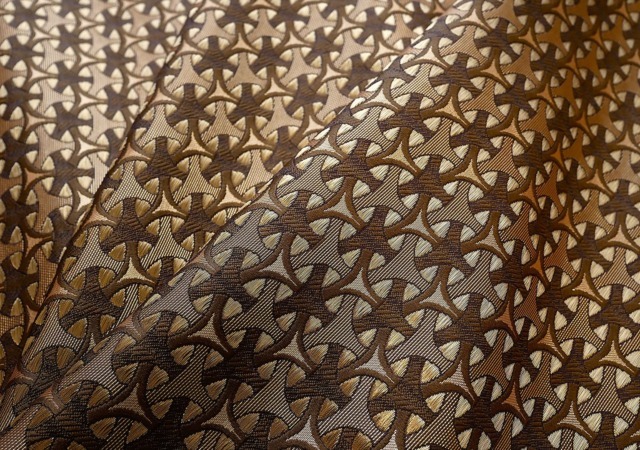

I like threads, or rather, I have been attracted to the process of weaving threads into a piece of cloth ever since I can remember. It takes a lot of help, but I really like making things that are completed in this way. Basically, we make only fabrics, so we rarely have a chance to see the finished products being used. I always wonder how they are used. When we wove a big Uchiki for a big temple, we were invited to go and see it with our family. I was very impressed with the quality of the work.

Nishijin is a town built on the division of labor, and it used to be very lively. The sound of machines could be heard everywhere. There was a job called “warp splicer,” who spliced new threads when the warp threads ran out, and an elderly man walked around the town to take care of the splicing. My parents told me, “If you have this skill, you can make enough money to support yourself even when you get old,” and I learned it, but nowadays machines are used for this job, and the job of warp thread splicing itself has disappeared. Although the mechanization of the crafts that used to be done by hand has made things more convenient, it is sad to see the decline in the number of craftspeople doing the work. There is a great sense of crisis when there is no one left to do the work and skills are lost. The people who make the small parts, the materials, and the indispensable items are disappearing rapidly. It would be nice if something could replace them and we could continue to make the same products as before.

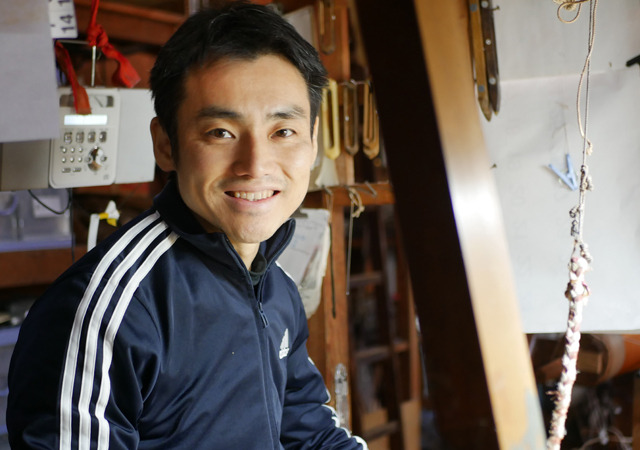

I was grateful when my son and his wife returned to the company just in time for the change from jacquard pattern card to floppy disks. Without my sons, we might not have been able to make the transition. When I think about it, it all comes down to timing. I am leaving the rest to the younger generation, but I hope that they will manage to preserve what needs to be preserved.

(Interviewed on November 13, 2023 / Text by Sakiyo Morimoto)

Want to discover more about the passion and craftsmanship of Nishijin Okamoto’s artisans?

Explore the timeless beauty of Nishijin-ori through exclusive interviews with the artisans behind it.

Check it out now!