We will be writing a two-part series on the history and characteristics of Nishijin Ori.

This installment is titled “The History and Characteristics of Nishijin Ori: Part B”. The previous installment was “The History and Characteristics of Nishijin Ori: Part A“.

History of Nishijin textiles

The origins of Nishijin Ori can be traced back to the Kofun period, between the 5th and 6th centuries. The Hata clan, who migrated to Japan, brought with them the techniques of sericulture and silk weaving.

These techniques developed during the Heian period in government-operated weaving workshops, leading to the formation of Oribe-cho, a town where artisans gathered.

During the Heian period (794–1185), silk fabrics such as kin (brocade), aya (twill), tsumugi (pongee), and ra (gauze) were produced for the imperial court and were cherished by nobility and royalty. In the Muromachi period (1336–1573), silk and twill produced in Otonericho were highly valued, leading to the formation of an organization known as “Otoneriza.”

After the Onin War (1467–1477), artisans who had sought refuge in Sakai, Osaka, returned to Kyoto and resumed their weaving industry in the Nishijin area, establishing intricate pattern weaving techniques. This period marked the foundation of what we now know as Nishijin Ori. The term “Nishijin” was derived from the Western Army’s camp location during the Onin War.

With the introduction of the draw loom, pattern weaving flourished, cementing the foundation of high-quality silk weaving known as Nishijin Ori. The Nishijin district was thus firmly established as a key production area.

Following the Meiji Restoration, Nishijin sent students to Lyon, France, to learn advanced weaving technologies, including the Jacquard loom. This modernization allowed Nishijin Ori to adopt its current characteristic of multi-variety small-lot production.

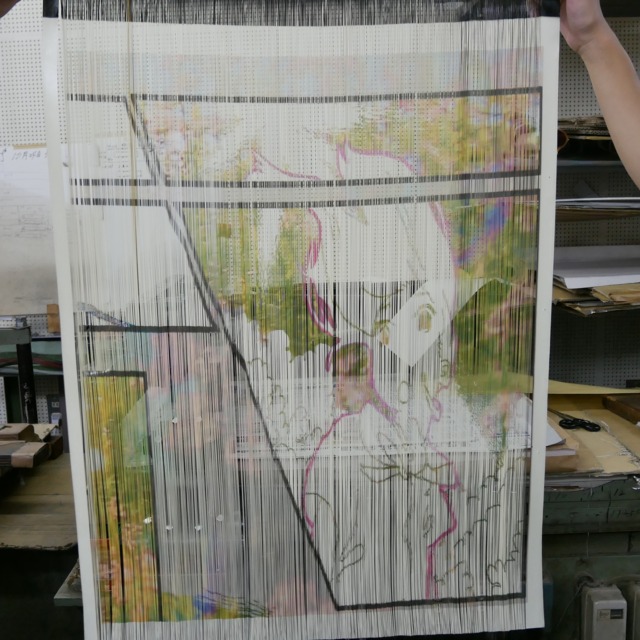

Before the Jacquard loom was introduced, the traditional draw loom (pictured below) was used. Today, this historical loom has been revived at the Nishijin Textile Center, while modern pattern weaving primarily uses hand looms equipped with Jacquard mechanisms, power looms, rapier looms, and air-jet looms.

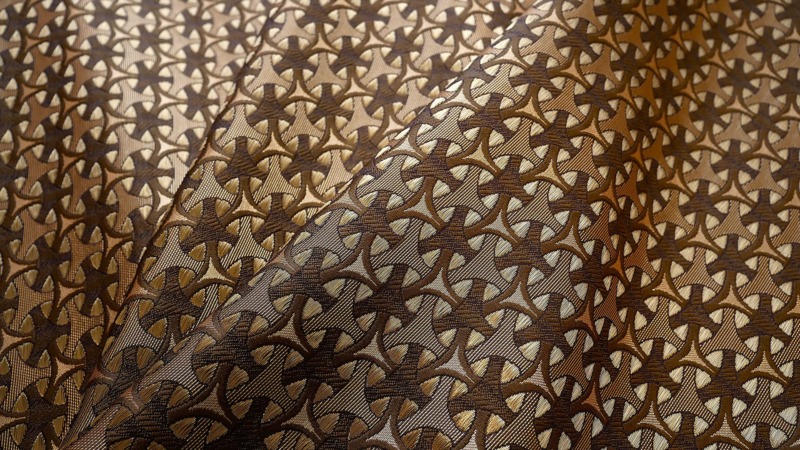

Even in modern times, Nishijin Ori is characterized by its multi-variety small-lot production.

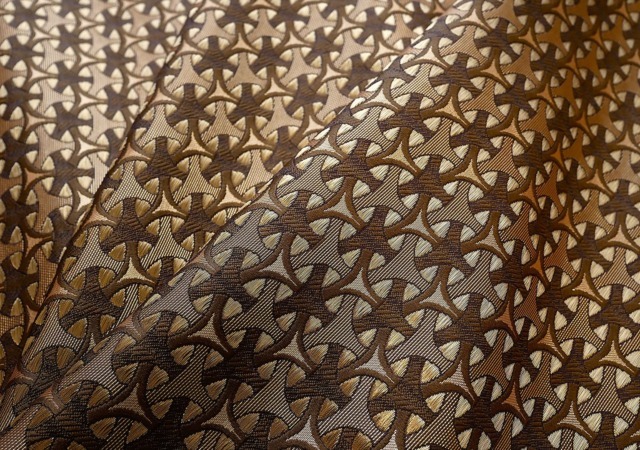

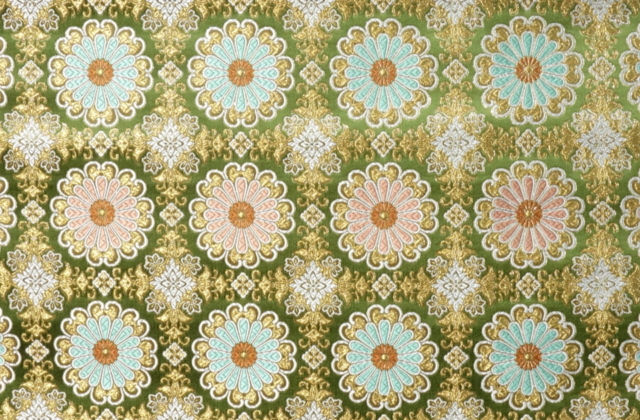

Nearly 300 weaving companies each employ their specialized techniques and materials to produce not only renowned obis, religious kinran, neckties, fabric for mounts, umbrellas, and shawls but also innovative products for interior applications. While preserving traditional materials and techniques, Nishijin continues to develop products that cater to new designs and uses.

Production Process (In Our Case)

Design Planning

Nishijin weaving involves using pre-dyed yarns to create fabric. Thus, planning a design that visualizes the final weave is crucial. A designer receives the order from the customer and creates a design based on the customer’s vision. This may involve multiple revisions to match the intended design.

Pattern Design Chart (Mon-Ishozu)

Next, a pattern design chart is created. The enlarged design is projected onto a grid-like paper (not square, but with a ratio matching the woven textile), and the pattern is traced in pencil. This process involves two steps: “Mawashi,” where the pattern is copied, and “Hatsuri,” where colors are filled in according to the grid. The squares indicate the warp and weft thread combinations for the Jacquard loom. Besides thread colors, the chart includes various instructions to facilitate weaving. Although digital tools like Photoshop are often used today, each dot of the design still needs to be carefully drawn.

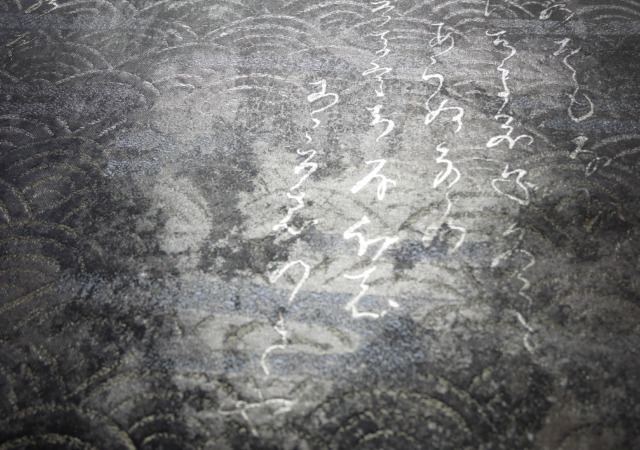

Monhori (engraving)

In order for the weaving machine to read the information on the design chart and weave the pattern according to the design, a process called monhori (engraving) is carried out. Monhori is a method of specifying information such as the position of the warp and weft threads up and down and the combination of coloured threads, square by square, by punching holes in a piece of paper called mongami. Holes were punched precisely using a machine such as a piano type mon-gami machine. Nowadays, computer graphic processing is widespread and crest paper is made as GGS data, rather than on actual paper. The picture below shows a small tissue pattern paper for our hand weaving and pre-machining machines. This does not contain enough information for weaving, so holes are punched by hand.

Twisted yarn

Preparation of silk threads. The silk is put through a process called twisting(nenshi). This involves twisting several silk yarns together and adjusting the thickness of the yarn. Twisting yarns of various thicknesses gives the Nishijin brocade its unique texture. Silk yarns of various thicknesses are used according to the product to be woven.

Thread dyeing

Silk yarns are sent out to be kneaded (refining). The dyer removes impurities from the silk yarn (natural impurities such as fibroin, a protein and sericin, a glue-like protein and wax) to produce a shiny white yarn. The yarn is then dyed to the colour ordered. As we dye many colours, we dye in small quantities, so the dyeing artisan’s intuition is very important.

Warp and weft reeling

Warp and weft yarns are wound onto a thread frame. In the past, the yarn was wound manually, but nowadays mechanical reeling is the norm.

Warp preparation

The thousands of warp threads required for weaving are wound onto a round tube called a ‘chikiri’ (beam), which is set on the loom, so that they can be woven in the required length. This process is called seikei.

Heddles

When the warp threads are set on the loom, they are threaded through the part called the heddle, which is made of thread and wire. This is an important step in weaving the warp and weft yarns into the intricate patterns of Nishijin brocade.

Weft winding

Yarn is wound around a thin bamboo-like tube for weaving into a weft.

Weaving

Weaving is done on hand looms, power looms, spelling looms, rapier looms and air-jet looms. Rapier and air-jet looms are used. Although rapiers and air jets have become popular in recent years, delicate weaving using a lot of silk, such as gold brocade, requires slow weaving on a hand loom or power loom.

Through these meticulous processes, Nishijin Ori continues to produce intricate textiles that captivate the world. By blending traditional techniques with modern needs, Nishijin Ori remains a symbol of Japanese culture, cherished by many to this day.

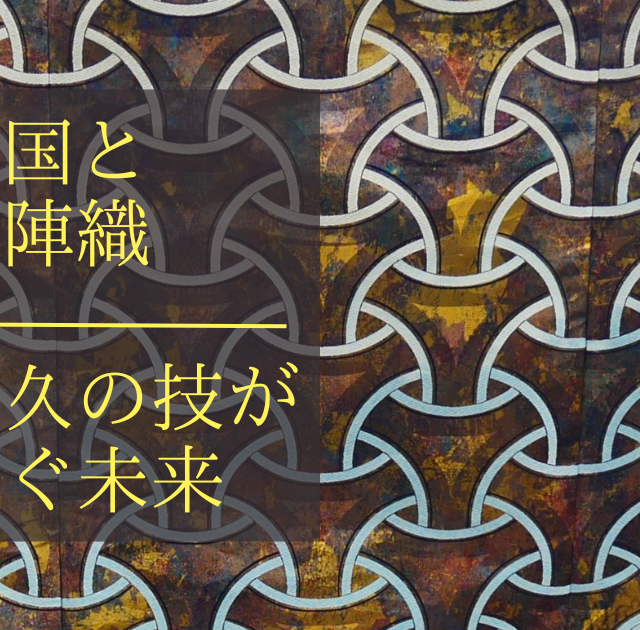

The Future of Nishijin Ori

Nishijin Ori is supported by a long history and advanced techniques. By incorporating new designs and technologies that meet modern demands, we strive to connect this tradition to the future. Additionally, we are committed to creating a sustainable production environment by giving back to the artisans and reducing the environmental impact on the region. While the beauty and technical sophistication of Nishijin Ori continue to symbolize Japanese culture, we recognize the necessity of taking new actions to preserve and pass on this textile for future generations.

I have divided the article on the history and characteristics of Nishijin Ori into two parts. The previous installment was “The History and Characteristics of Nishijin Ori: Part A,” and this current installment is “The History and Characteristics of Nishijin Ori: Part B.” I hope that through these articles, you will come to appreciate the history and production process of Nishijin Ori. If you are interested, we sincerely hope you will have the opportunity to see these exquisite textiles in person.

“The History and Characteristics of Nishijin Ori: Part A“

“The History and Characteristics of Nishijin Ori: Part B”

References: Nishijin Tengu Writing Stories: A Personal History of Nishijin, Koma Toshiro.