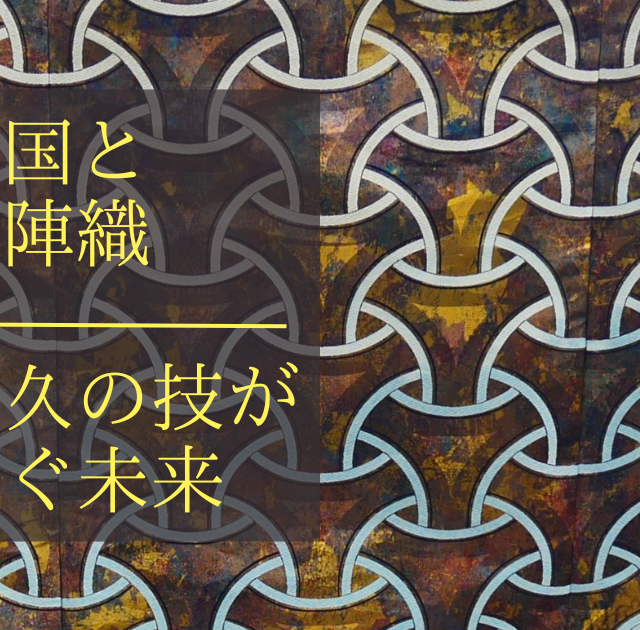

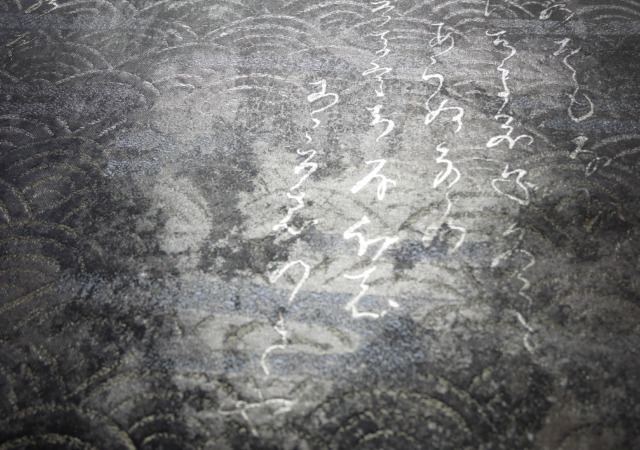

Seikei, or warping, is the process of preparing the warp threads for Nishijin weaving. It is a crucial technique that directly affects the quality of the final textile. Though rarely seen on the surface, the world of warping behind Nishijin textiles plays a vital, behind-the-scenes role in supporting the culture of weaving.

Nakagawa Seikei – Masafumi & Hiroko Nakagawa

“I want to warp the threads so that the weavers can work easily. I always try to be meticulous.”

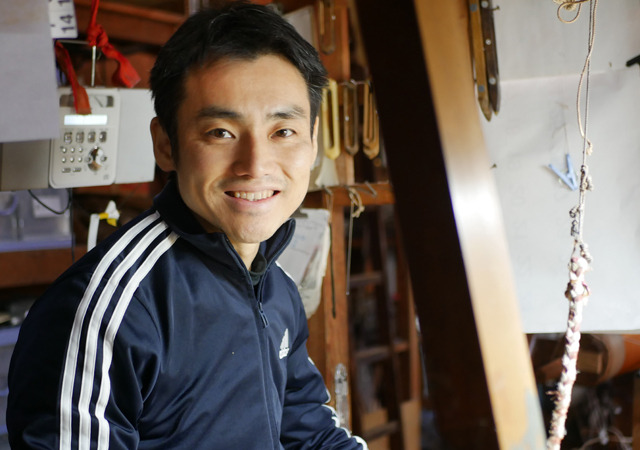

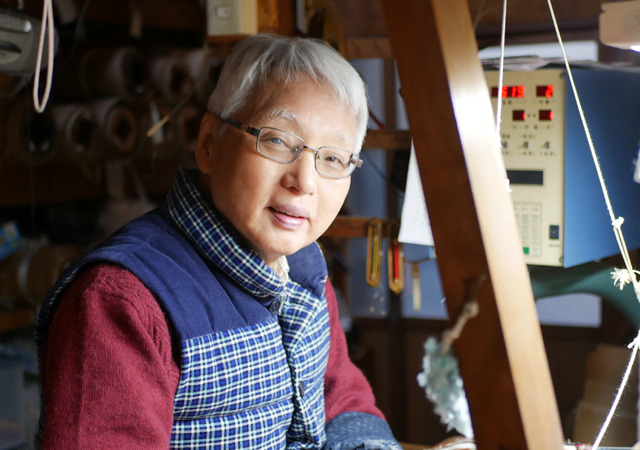

These are the words of Masafumi Nakagawa, a warping artisan for Nishijin textiles. As the second-generation head of Nakagawa Seikei, founded in 1937 in Kyoto’s Nishijin district, he has devoted his life to this craft. Together with his wife Hiroko, they work side by side to support the foundation of textile beauty.

What is Warping?|The Most Critical Step in Weaving

To begin, please watch the video we filmed at Nakagawa Seikei:

YouTube Video: The Craftsmanship Behind Nishijin Weaving|Filmed at Nakagawa Seikei

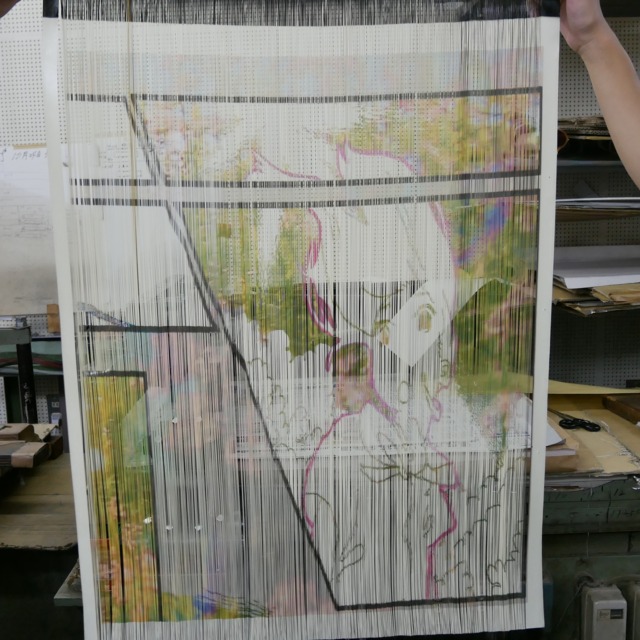

When weaving fabric, it’s essential that the warp threads are aligned without distortion or slack. Warping is the process of preparing these threads so they can be woven smoothly. It’s an indispensable technique not only for Nishijin weaving but for all woven textiles. One particularly important aspect is the “aze,” a method of aligning adjacent threads to prevent tangling. Though invisible in the final product, this technique is what supports the beauty of the textile from within.

What is “Aze”?

“Aze” refers to the part of the warp where each thread is crossed and held in place to maintain its order during weaving. It may look simple, but maintaining this alignment is critical. The following video, produced by the Kyoto Textile & Machinery Promotion Center in Kyotango—famous for Tango Chirimen—explains how aze is formed. It’s very easy to understand, so please take a look:.

The aze is formed at the beginning of the warping process. Here is a video showing how it’s done at Nakagawa Seikei:

Nakagawa Seikei – A Nishijin Warping Studio

Nakagawa Seikei was founded in 1937 (Showa 12). Today, Masafumi Nakagawa, the second-generation artisan, carries on the tradition. His grandfather originally ran a weaving studio, but due to shifts in textile demand following the Manchurian Incident in 1931 and the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the family transitioned into warping.

Hiroko-san winding silk threads, carefully watching for any irregularities.

Growing Up as a Nishijin Warping Artisan

“I grew up with the sound of warping machines,” Masafumi-san says with a smile. After graduating high school, he worked for two to three years with his older brother as an electrician. Eventually, he returned to the family business of warping. Having lived and worked in the same space since childhood, he naturally absorbed the skills without formal training and began working without hesitation.

In his younger days, he worked from early morning until late at night, drawn in by the fascination of warping. After marrying Hiroko-san, she joined him in the work, handling thread winding and helping to sustain the family business together.Hiroko-san winding silk threads, carefully watching for any irregularities.Hiroko-san winding silk threads, carefully watching for any irregularities.

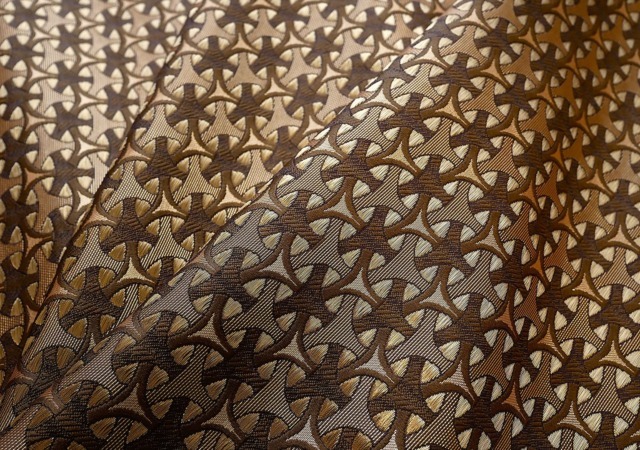

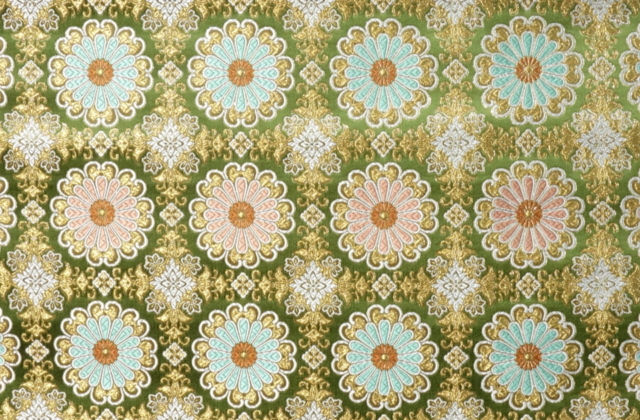

Over the years, Nakagawa-san has worked on a wide variety of warping projects. From our own Nishijin brocade fabrics to Taisho Roman-style obi belts, the long trailing obi worn by maiko, and striped or kasuri-patterned warps—he has adapted to the trends of each era. One memorable story he shared was about creating striped warp threads:

About Warping

Here’s a video explanation of the warping process. On the day of filming, Nakagawa-san was preparing warp threads for obi fabric. Obi fabric is narrower than our brocade width, and often uses white or black warp threads with color expressed through the weft. In this case, he was making white warp threads. We hope you’ll enjoy the detailed steps and the beauty of the artisan’s handwork.

1: Winding silk from skein to wooden frame

2: Guiding the wound silk threads to the warping machine

3: Aligning the aze while warping the threads

4: Winding the silk threads onto the beam

Nishijin-specific terms like “katsu” and “suga” are explained in this guide from the Nishijin thread supplier Yoshikawa Shoji:

Industry Changes Through Experience

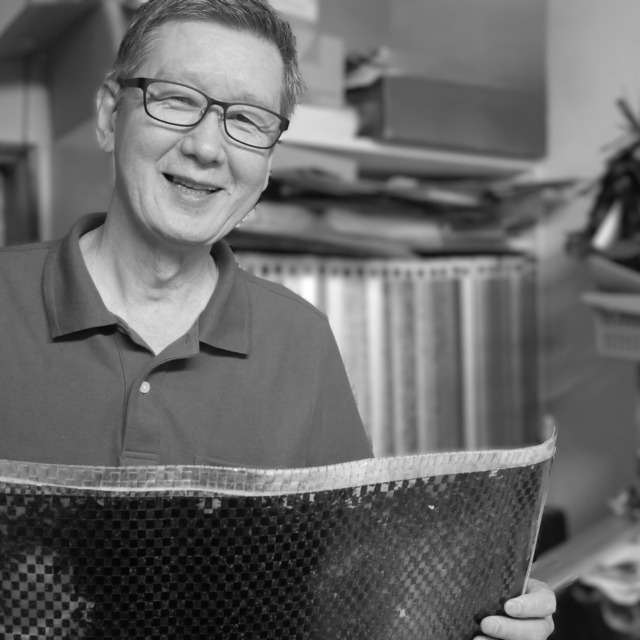

Now in his 70s, Nakagawa-san has begun to reduce his workload. He also spoke about the challenges of passing on the craft to the next generation:

His words reflect the artisan’s intuition—skills cultivated through observation and analysis rather than instruction.

Involvement in Imperial Ceremonial Attire

Among the most memorable projects for Nakagawa-san was warping threads for ceremonial garments used by the Emperor and Imperial family, as well as for the Shikinen Sengu rituals.

“I never get to see the finished pieces,” he says, “but knowing that my work is used in such prestigious settings fills me with pride.”

Challenges in the Modern Era

Nakagawa-san also shared concerns about changes in thread quality, the dyeing techniques of dyers, and the lack of deep understanding among younger weavers. As a self-employed warping artisan, he spoke candidly about stagnant pricing and the need to rethink the current system:

If Nishijin weavers want to preserve this industry, they need to raise the prices for the work that comes before weaving.

Nishijin operates on a division of labor. Even though warping artisans are self-employed, we’re subcontractors to the weavers.

I think it was a mistake that the weavers didn’t nurture their subcontractors.

The idea that it’s fine as long as your own business profits—that’s not right.

When I was young, even though the unit price was low, I could make a good living by doing a high volume of work.

I earned more than ten times what my university-graduate friends did.

But if you’re setting up large machines at home, going around to collect threads from weavers, and delivering the finished beams—with no retirement benefits like a company employee—then earning the same as a salaried worker isn’t enough.

You need to earn significantly more than that for it to be worthwhile.

Nowadays, it seems salaried workers aren’t allowed to work more than eight hours a day,

but even as an old man, I still work more than eight hours.

What will the future look like, I wonder?

“What do I think is necessary to pass on Nishijin’s techniques to the next generation?”

If Nishijin weaving is to survive as a production region, we need to change many aspects of the system.

(Interview conducted on July 31, 2025 / Text, photos, and video by Ema Okamoto)

Editor’s Note

As someone who works at a Nishijin weaving studio, I see warp threads on the loom every day.

These threads are first purchased from thread suppliers, then handed to warping artisans, and finally returned to us wound onto beams (“chikiri”).

This was my second visit to Nakagawa Seikei.

The first was when I filmed my very first video, “From Thread to Textile: The Journey of Nishijin Weaving”.

It was my first time seeing the large warping machine spinning, winding threads with precision.

Compared to the small hand-warping frame I use for personal weaving, I could immediately sense how this process creates warp threads that are truly easy to weave.

During the interview, the Nakagawas warmly welcomed me.

We often see each other when they come to pick up silk threads or deliver the warped beams, but we rarely get a chance to talk.

This interview with the charming and talkative couple ran long—but it was a delightful time.

In this series of interviews, I’ve visited a thread supplier, a dyeing studio, and a warping artisan. It’s reaffirmed my belief that weaving begins and ends with thread.

Next time, I’ll share the voices of artisans who create hikibaku (metallic foil yarn).

Explore past artisan interviews here: