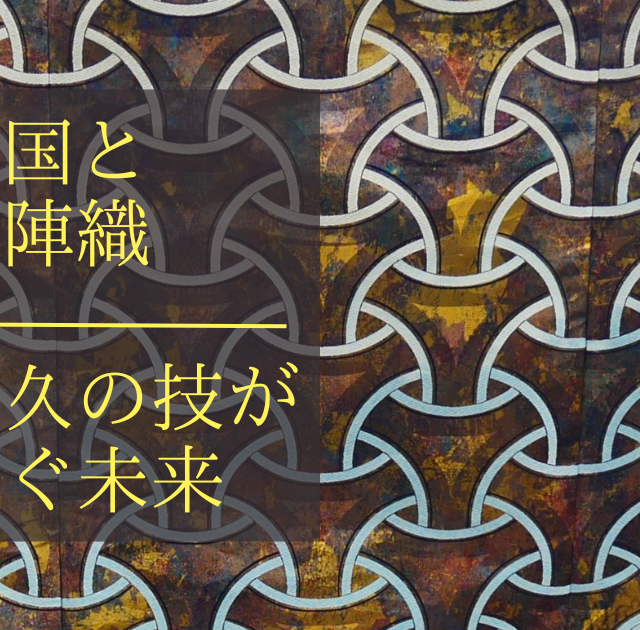

Enhancing the Beauty of Nishijin Weaving|The Pride of a “Hari-ya” – Higuchi Kinran Seiriteiten

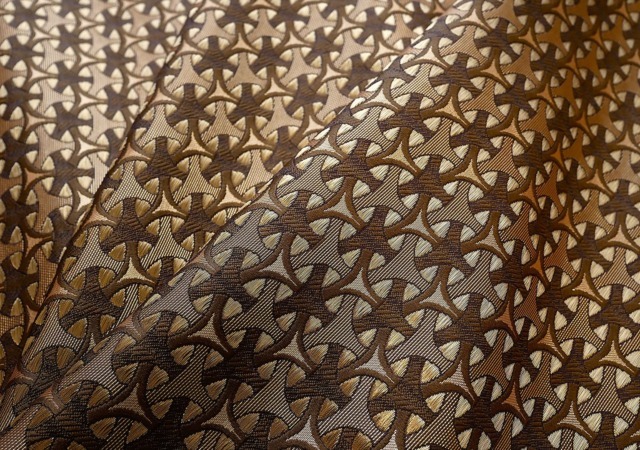

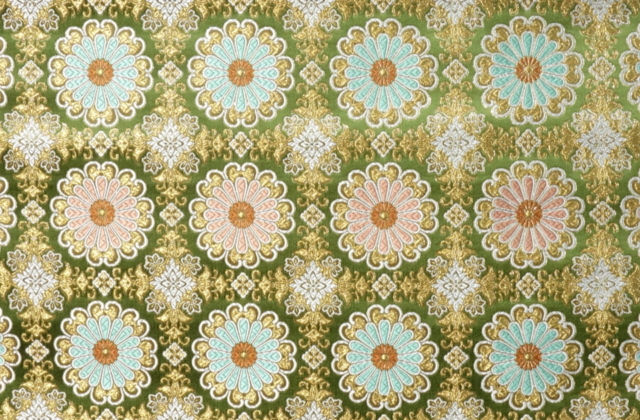

Among the artisans who support Kyoto’s Nishijin textile culture, have you heard of the “hari-ya”? These specialists apply starch to finished kinran brocade, refining the texture and strength of the fabric. It’s a vital process that brings out the full beauty of the weave.

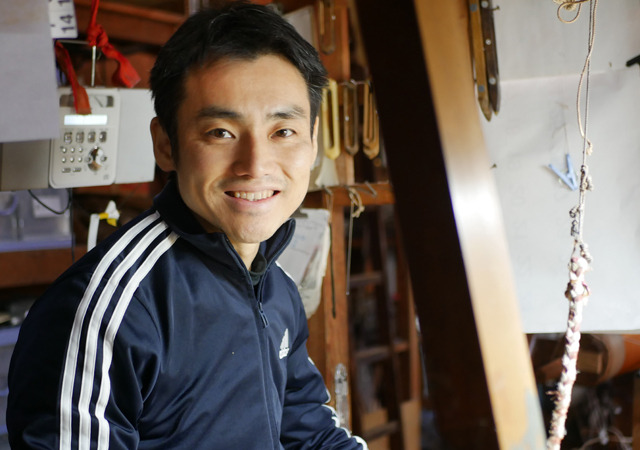

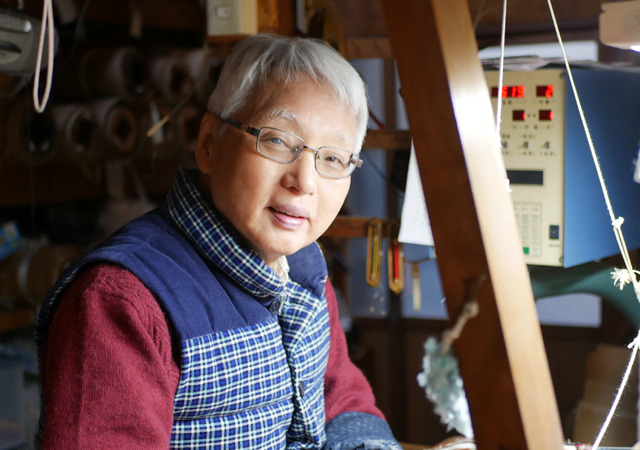

This time, we spoke with Toshiyuki Higuchi and his wife Akiko, who have carried on the work of starching for three generations at Higuchi Kinran Seiriteiten.

Higuchi Kinran Seiriteiten Toshiyuki Higuchi and Akiko Higuchi

- Family Trade – The Origins of a “Hari-ya”

- From Office Worker to Artisan – A Turning Point and a Decision

- Technique Passed Down Through Sound and Sensation

- Venturing into Nihonga – The Challenge of Dosa Application

- Funori and Rice Starch – A Commitment to Materials

- Memorable Work – From Sumo Belts to Tatami Edging

- Passing on the Craft – Collaboration Beyond Boundaries

- Responsibility and Pride – Being Part of the Flow

Family Trade – The Origins of a “Hari-ya”

Toshiyuki’s grandfather was born in 1898 (Meiji 31). As a young man, he apprenticed at a starching shop and learned the craft. It was a time of transition from handlooms to power looms. While handlooms applied starch during weaving, power looms required starching after the fabric was woven. As power looms became more common, so too did the need for “hari-ya.”

“I heard my grandfather was working here around the late Taisho or early Showa period,” Toshiyuki recalls. After the war, his father took over as the second generation, and Toshiyuki himself returned to the family business around 1989, becoming the third-generation artisan.

Later, in the 1940s, my father took over as the second generation. It was right after the war, and jobs were scarce, so he continued the family trade.

I started out as a company employee. But I’d always seen this work growing up, so I figured I’d eventually take it on. I returned to the business around the end of the Showa era, in 1989. So I’m the third generation, and this is my 37th year as a ‘hari-ya.’

From Office Worker to Artisan – A Turning Point and a Decision

“I used to work in convenience store logistics. It was a time when we were opening multiple new stores every month.”

As an area manager, Toshiyuki was constantly busy. But after falling ill from overwork, he began to reflect on his life and marriage, ultimately deciding to return to the family business. “Back then, Nishijin was still thriving. When I consulted my father, he said, ‘You’ll be fine coming back.’”

Today, he continues the work side by side with his wife Akiko.

Technique Passed Down Through Sound and Sensation

The distinctive “shaa” sound of starch being spread with a spatula—captured vividly in video—is unique to the hari-ya’s workshop.

There’s no manual for this. You learn by doing. There’s a kind of sensation that’s hard to put into words. Things like temperature and humidity—it’s not something you can easily explain.

I was born and raised in the workshop, so I’ve understood what we do here since I was a child.

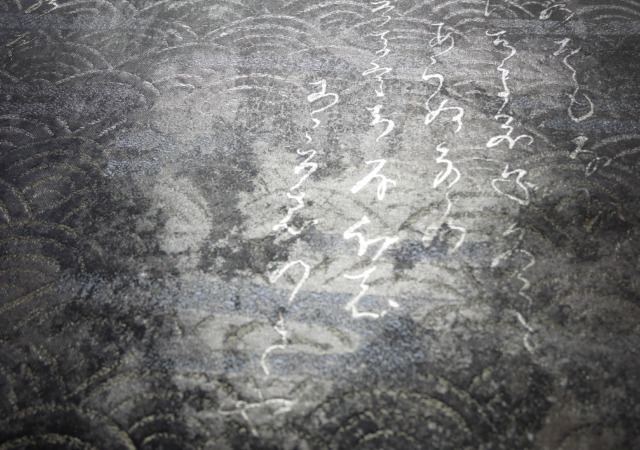

Venturing into Nihonga – The Challenge of Dosa Application

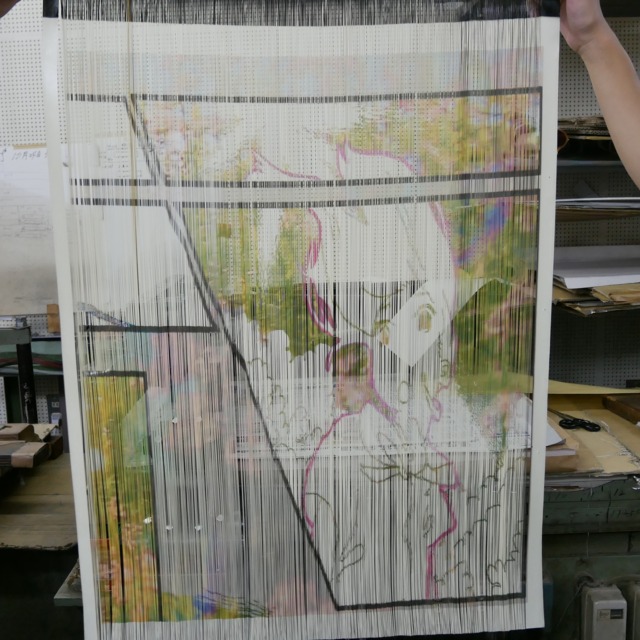

In recent years, Toshiyuki has taken on a new challenge: dosa application. This process involves coating silk for painting (e-ginu) with a mixture of animal glue and alum to prevent pigment bleeding.

It’s a process where you coat thin silk with glue and alum to prevent ink and paint from bleeding.

Unlike kinran, which is about 70 cm wide, this silk is about 3 shaku (roughly 90 cm) wide. I had no idea how to stretch it, what to apply, or how it was done. I started from scratch, experimenting through trial and error.

The artisan who used to do it had retired without training a successor. No one had documented the process—not even videos. No tools were left behind. I didn’t even know if they used shinshi rods.

So I kept trying and asking, “How about this?” over and over.

Old-school artisans used to learn by watching, so nothing was written down. Now, alongside kinran starching, I also do dosa application for Nihonga.

Machines can handle some tasks, but there are parts that only human hands can manage.

Even in Nishijin, we face issues like loom parts becoming unavailable. When something breaks, we salvage parts from old machines. It’s tough, and I think our industry faces similar challenges in maintaining tradition.

Funori and Rice Starch – A Commitment to Materials

The starch used is made from funori (a seaweed) and rice starch. Funori comes in dried sheets, which are slowly simmered over low heat into a paste. It’s stored in the fridge and used as needed. Written in kanji as “布海苔,” funori has long been used in textiles—and it’s delicious, too!

The photos show, from left to right: sheet funori, simmering funori, and kneading the paste. Photo: Socca Co., Ltd. 2017

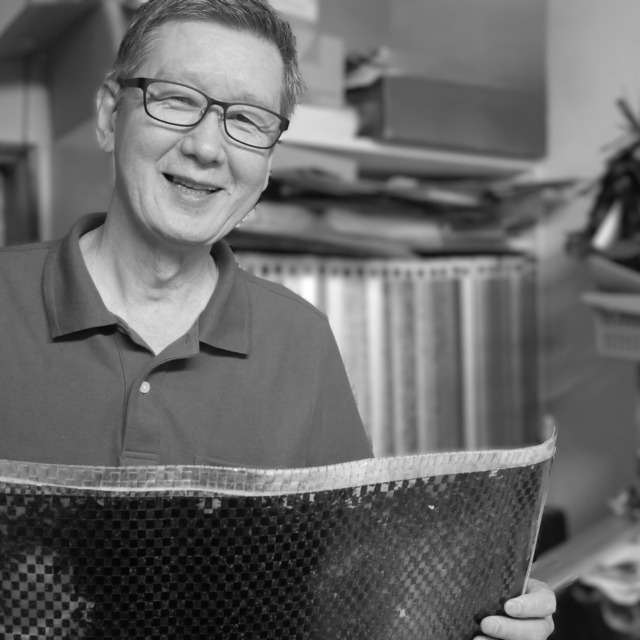

Memorable Work – From Sumo Belts to Tatami Edging

Sumo belts, shrine decorations, tatami borders—the work of a hari-ya appears in many places people encounter.

If it looked short, it was probably Mainoumi’s. If it was huge, it was Akebono’s. Mainoumi’s was about 7 meters, Akebono’s was around 13. The difference was striking.

There was a rare silver juniper-colored belt once. Most are navy, purple, or black, but that one belonged to a wrestler named Musōyama.

I remember watching sumo broadcasts and hearing the announcer say, “He’s wearing a silver juniper belt,” and thinking, “That’s my work.”

When I visit shrines or attend funerals, I sometimes think, “Ah, I did that piece.”

Passing on the Craft – Collaboration Beyond Boundaries

“Our job is to responsibly process the items entrusted to us and return them in proper form. That’s everything.”

As someone involved in Nishijin, Toshiyuki emphasizes the need for cooperation across companies.

“Even if we can’t do something here, maybe another workshop can. I hope the weaving industry becomes one where we pass work between each other. We need to help one another. I want this to be a field where routines can be sustained.”

Responsibility and Pride – Being Part of the Flow

With 37 years of experience, Toshiyuki’s words carry the pride and responsibility of a true artisan.

Behind the beauty of Nishijin weaving lies the quiet passion of craftspeople like him.

(Interviewed on September 6, 2025 / Text by Ema Okamoto)

Editor’s Note

I’ve been visiting Mr. Higuchi since shortly after joining the company. I remember feeling a deep sense of Kyoto when I first saw the starching process. Back then, his parents were still active, and the whole family worked together. Since then, I’ve been grateful for their support both professionally and personally.

Starching is surprisingly difficult—it must never affect the surface, yet penetrate just enough. It requires true skill. The method also changes between summer and winter fabrics. Now that Mr. Higuchi has begun dosa application for painting silk, I sense this new path will continue to grow.

In this series, we’ve visited thread makers, dyers, warpers, foil artisans, cutters, designers, and starchers. Thanks to these artisans, our weaving work is possible. Next time, we’ll share the voices of the weavers who use power looms to produce our kinran fabrics.

For a full list of artisan interviews, click below: