The Artisans Behind Nishijin’s Rare Technique: Hikibaku Cutting

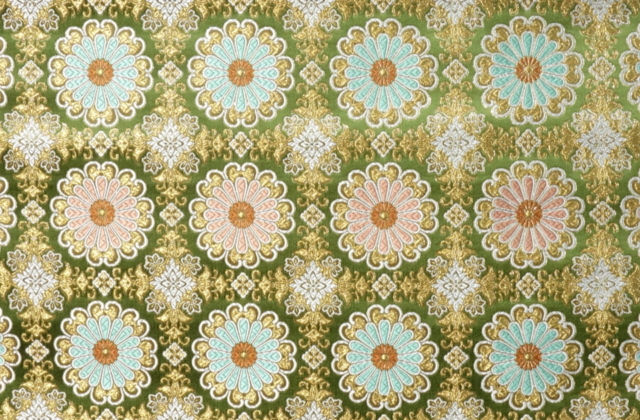

Kyoto’s Nishijin district is home to a refined textile tradition. Among its many intricate processes is the cutting of “hikibaku”—a technique that evolved uniquely in Nishijin from methods originally introduced from China.

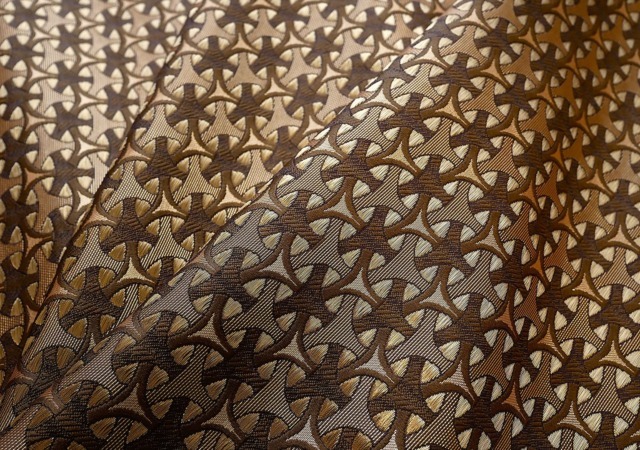

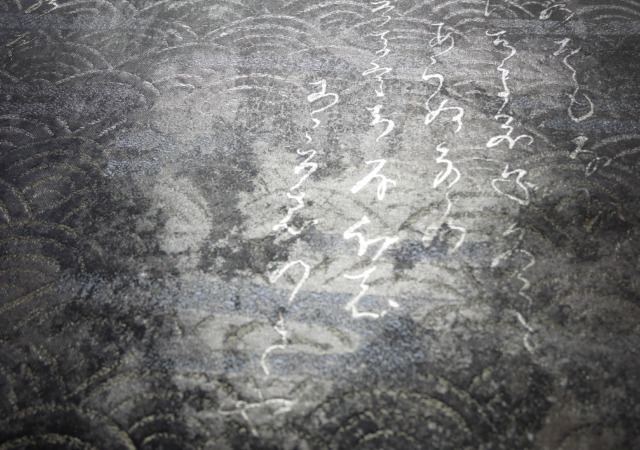

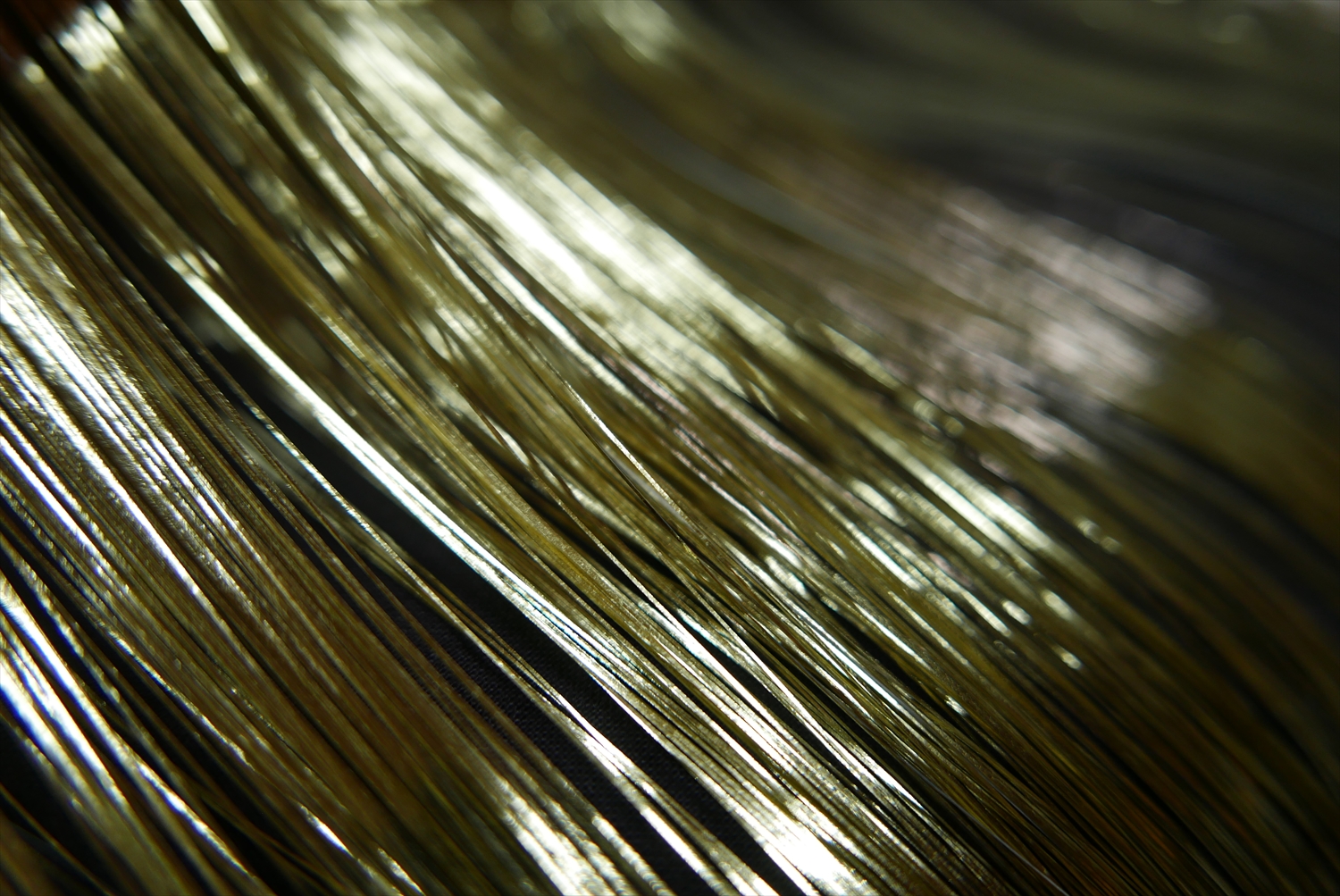

Hikibaku refers to washi paper coated with lacquer and layered with gold or silver foil. This rare material is used as weft threads in obi and kinran fabrics. The delicate and precise cutting of hikibaku is the specialty of Takeuchi Cutting Studio. Since the postwar era, they have upheld this process, and today, only a handful of artisans remain who possess this skill. Within Takeuchi’s workshop lives a quiet pride and unwavering commitment to preserving the beauty of Nishijin textiles.

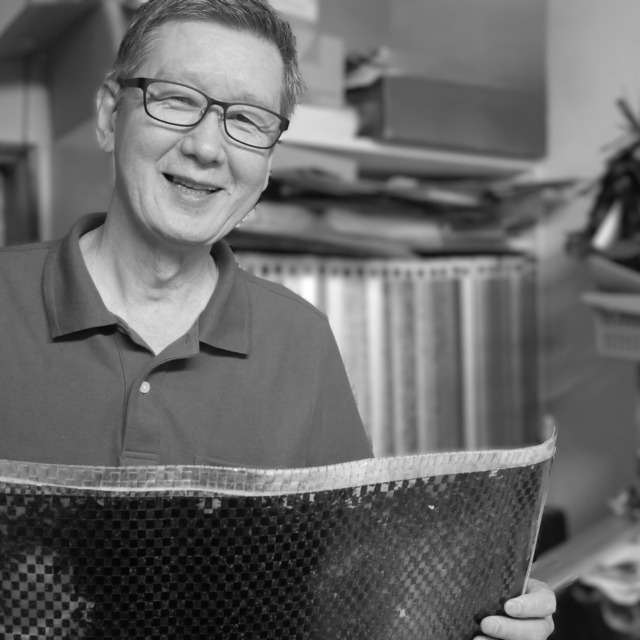

Takeuchi Cutting Studio – Mr. Katsuyoshi Takeuchi

Cutting with Care for the Weavers

The cutting machine, nicknamed “guillotine,” may appear bold, but it was custom-built to handle delicate materials without damage, meeting the specific needs of each client. Though it looks rugged, without meticulous maintenance and adjustment, it cannot produce threads suitable for weaving. Daily oiling and blade tuning are essential.

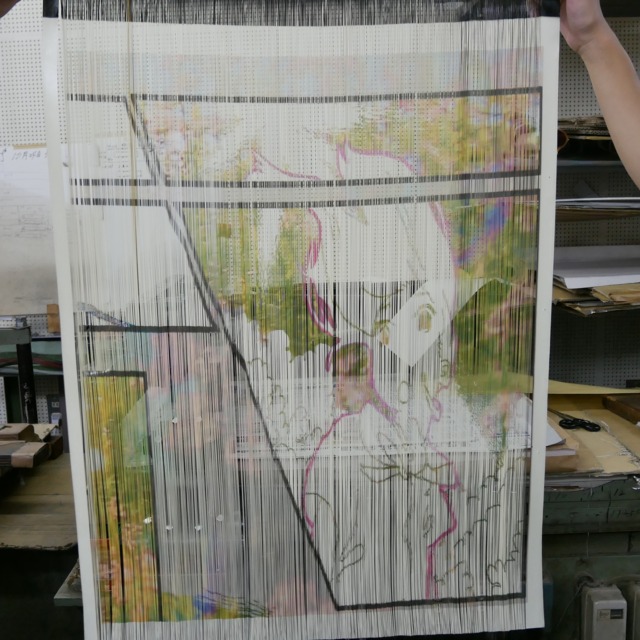

The most crucial part of hikibaku cutting is the preparation. Sheets of paper are layered—many upon many—with hikibaku paper placed in the middle, then more layers added, lubricated with white oil (sewing machine oil), and further layered again. The time spent ensuring the stack is even and immobile reminded us that preparation is everything.

Mr. Takeuchi’s words reflect years of experience and a deep respect for the craft.

Please watch the video below to see the hikibaku cutting process in action. Hikibaku is a thread-like material made by cutting lacquered washi layered with gold and silver foil.

This video documents Mr. Takeuchi’s demonstration of the cutting process. Witness the artisan’s skill in handling such delicate materials.

From Hand-Cutting to Machine Precision

Takeuchi Cutting Studio was founded after World War II. Mr. Takeuchi’s father had worked as a foreman in foil cutting before the war. At that time, all foil was cut by hand. After the war, he resumed work under his master and eventually transitioned to machine cutting. When viewing old kinran fabrics, you can see that the foil was not as straight as it is today.

From obi widths to kinran widths, 120cm rolls, and even long slits for warp threads—the cutting method and machinery change depending on the intended use. Inside the workshop are various machines, each designed to meet the diverse, small-lot production needs of Nishijin weaving.

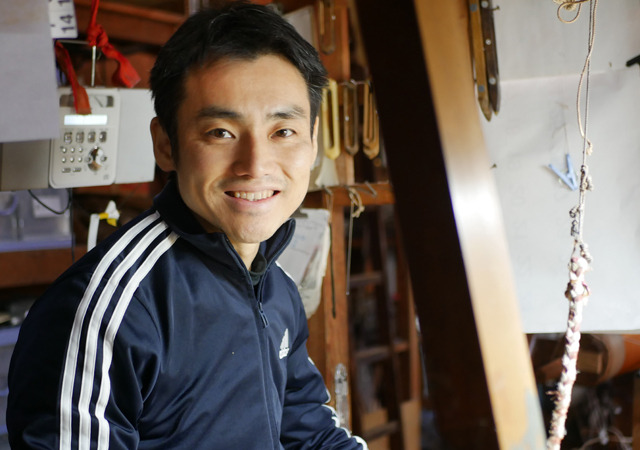

Sound, Memory, and the Artisan’s Path

Mr. Takeuchi first encountered the hikibaku cutting process as a child in kindergarten. One of his earliest memories, at age three, is the sound of foil being sliced.

After graduating high school, he naturally joined the family business amid a labor shortage. But the training was far from easy.

Back then, skills were “stolen with the eyes.” In that era, Mr. Takeuchi quietly mastered the art of cutting through observation and persistence.

Foil as Warp Threads—The Memory of “Tatesaga”

In his early days, Mr. Takeuchi worked not on weft hikibaku threads, but on warp foil threads known as “tatebaku.” This process was called “tatesaga,” short for “tatebaku Saga-nishiki.”

What is “Tatesaga” (Tatebaku Saga-nishiki)?

- It is a traditional textile technique passed down in Saga Prefecture.

- Uses foil threads made from cut washi paper as warp threads.

- Silk threads are used for the weft.

- Even when woven in Nishijin, it is still called “Saga-nishiki” because the technique and materials follow its definition.

- It is an extremely rare textile, with only a small amount woven per day.

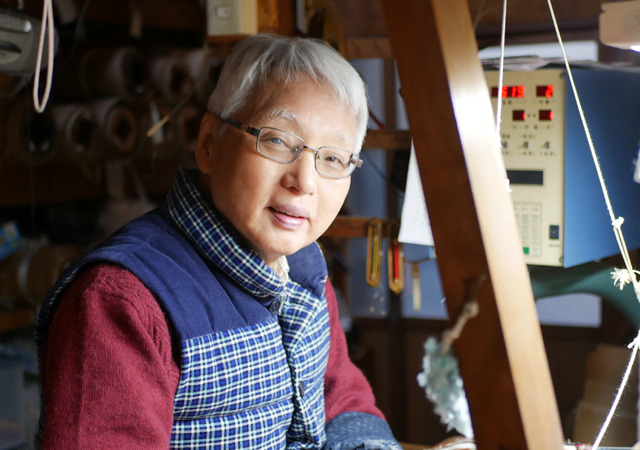

The work of “tatesaga” continued until the early Heisei era, but eventually ceased due to declining demand. Today, no artisans in Nishijin cut foil for “tatesaga.”

The Responsibility of the Final Process

Mr. Takeuchi’s current main work is cutting foil for hikibaku. Because he handles pure gold hikibaku, extreme care is required to avoid damage.

We cut pure gold hikibaku—washi coated with lacquer and layered with gold foil. We’re the final step in the process. If the blade has even a tiny nick, or if metallic grit remains in the paper (invisible grains sometimes remain in washi), it can cause scratches.We cut 50 sheets at once, so if one gets scratched, the whole batch becomes unusable. If I sense something’s wrong, I stop the machine immediately and adjust the blade. Otherwise, everything could be ruined.

If all the sheets are damaged, it could lead to compensation claims worth hundreds of thousands of yen. That’s the hard part.

Regarding metallic grit in the paper, Mr. Takeuchi shared:

Compared to the past, washi has less metallic grit now, making things easier. In the old days, invisible sand-like particles would get mixed in during papermaking. You couldn’t see them, but once you cut, the blade would hit them and get damaged.The blade hits the grit and presses down—that’s where the scratch happens. The grit chips the blade, and then scratches appear one after another. So I remove the blade and sharpen it again. Not with water, but with oil. There’s something called an “oil whetstone.”

Nowadays, with less grit in the washi, it’s much easier.

Blade adjustment and oil whetstone sharpening—these invisible grains that chip the blade are a shock even for Mr. Takeuchi. That’s why he emphasizes careful work, so weavers can use the threads with confidence.

Change and Continuity

At its peak, there were six workshops and over 20 artisans specializing in hikibaku cutting. Today, only three remain—including Mr. Takeuchi. He expressed a desire to continue as long as possible, but also shared a sobering truth for Nishijin weavers.

Right now, I’m the only one who can cut hikibaku. Mr. Nakajima is still around, but he’s quite elderly.I wish someone would take over, but it’s hard to find such people. Our work requires large machines and spacious facilities, and sometimes even involves liability issues. In the past, we had enough volume to make it worthwhile, but now, with fewer orders and unchanged wages, it’s no wonder no one wants to take it on. This is something the industry really needs to think about.

The beauty of Nishijin weaving is not created by the weavers alone—it is supported by artisans like Mr. Takeuchi, working behind the scenes. Though rarely seen, the work of Takeuchi Cutting Studio forms the backbone of Nishijin’s finest hikibaku textiles.

Takeuchi Cutting Studio Co., Ltd.

Location: 23-12 Shimogoshicho, Murasakino, Kita-ku, Kyoto City, Kyoto Prefecture

(Interview conducted on August 20, 2025 / Text, photos, and video by Ema Okamoto)

Editor’s Note

We previously interviewed Mr. Takeuchi for the video

“From Raw Materials to Completion: Nishijin Kinran Tapestry with Pure Silver Foil and Pearl Powder”.

When I contacted him again saying, “We’d love to film another video,” he kindly agreed to let us document the hikibaku cutting process used for our “MANGA × Nishijin Weaving” project.

I told him, “We want to see the most challenging part of the process,” and he replied, “Then you’ll need to see it from the very beginning.” Though I worried about intruding, he generously allowed us to observe the entire process from start to finish.

Layering sheets of paper without any unevenness, adjusting the blade gently yet precisely—watching this, I was reminded once again:

The true beauty of textiles resides in the invisible processes behind them.

As part of the “MANGA × Nishijin Weaving” production, we visited

the thread maker, the dyer, the warper, the foil artisan, and the cutter.

Through these interviews, we’ve come to reflect on how Nishijin weaving has evolved, where it’s headed, and most fundamentally—what Nishijin weaving truly is.

Next time, we’ll feature an interview with “Granuto,” a 19-year-old creative unit bridging tradition and pop culture.

We’re excited to see what fresh perspectives they bring to Nishijin weaving.

You can view all past artisan interviews here:

Here is the hikibaku cut by Mr. Takeuchi for the “MANGA × Nishijin Weaving” project:

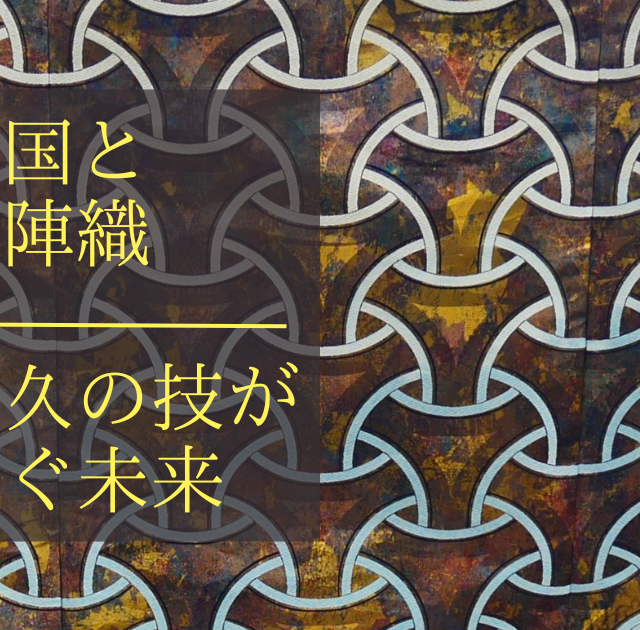

This collaborative Nishijin Kinran tapestry—featuring pure silk and hikibaku patterns designed by young manga creators “Granyuto”—will be exhibited from October 3 at the

2025 Japan International Expo “Osaka-Kansai Expo” in the EXPO Messe “WASSE” pavilion.

We hope you’ll visit

“Future Voyage – The Journey of Small Businesses Toward 20XX”,

an experiential exhibit at the 2025 Osaka-Kansai Expo.