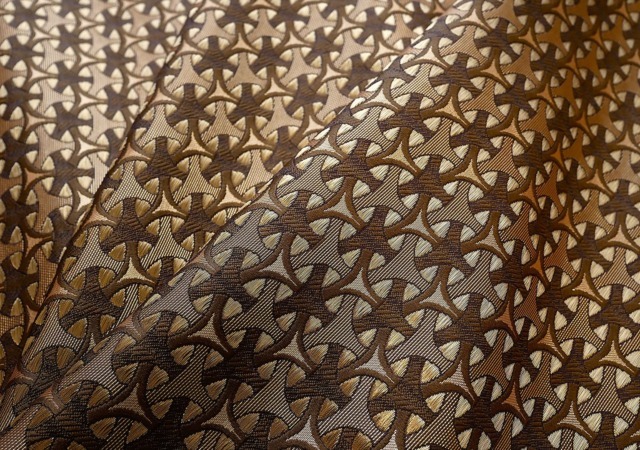

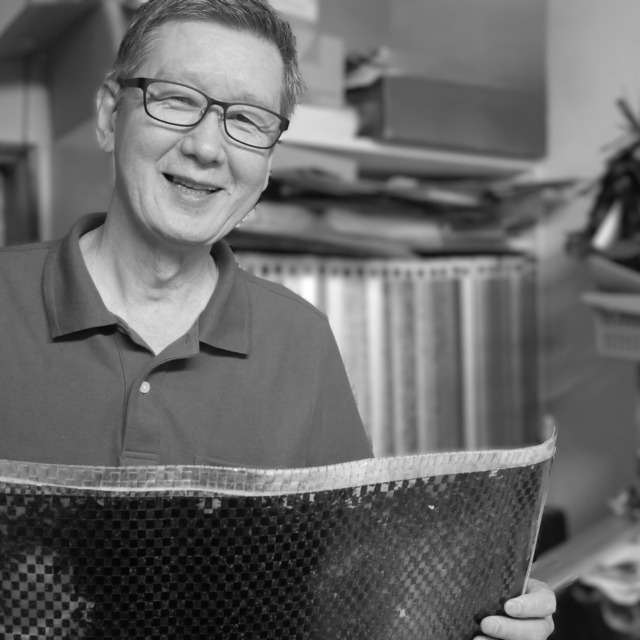

Nishijin Okamoto known for weaving Nishijin kinran brocade in Kyoto’s Nishijin district, is supported by a cooperative workshop in Kyōtango called Nunohira. There, a weaver who grew up surrounded by the sound of looms continues the craft. In this interview, we spoke with Mr. Katsuhisa Nunohira and his wife Sachiko—Nishijin kinran weavers—about the origins of their family trade, their current techniques, and their hopes for the future.

From the Power Looms of Nishijin Weaving Mr. Katsuhisa and Ms. Sachiko Nunohira

The Sound of Weaving as a Lullaby – A Family’s Origins

“The sound of the loom was like a lullaby to me. I couldn’t sleep without it,” says Mr. Nunohira. His grandparents were farmers, but when his mother began weaving after marriage, the family’s path shifted toward textiles. Childhood memories of his mother weaving remain deeply rooted as the foundation of his craft.

Weaving began in our household when my mother married into the family. My grandfather’s generation was engaged in farming, with rice fields and vegetable plots a short distance from the house. I’m the ninth generation, and my father’s generation became part-time farmers.

My mother had woven chirimen before marriage, and she continued weaving after joining our family. Eventually, my father joined her, and they began weaving wool kimono fabric.

When I was in elementary school, we started weaving narrow-width textiles for items like zōri sandals and handbags. Then, 31 years ago, we began weaving kinran brocade for Okamoto.

A Natural Path into Weaving – Entering the Craft After High School

During Japan’s economic bubble, the textile industry experienced a boom often called the “return of Gachaman”—a time when demand was so high that no amount of weaving seemed enough. As the previous generation expanded the workshop and installed new looms, Katsuhisa decided to carry on the family trade.

When I was in high school, my father expanded the workshop and added two looms. Since they needed someone to operate them, I entered the world of weaving right after graduation.

Inherited Techniques – Nishijin Weaving Passed Down from Mother

Katsuhisa learned weaving from his mother, who had experience weaving Tango chirimen before marriage. Her skill in handling silk laid the foundation for Nunohira’s current techniques, which now support Okamoto Orimono’s high-end Nishijin kinran production using shuttle power looms.

When our company appeared on the regional program Kyoto Chishin, which focuses on “tradition and innovation in Kyoto,” Katsuhisa’s mother, Hatsumi-san, also appeared. Around 5 minutes and 30 seconds into the episode, you can see weaving scenes at Nunohira. It was filmed in 2019—a nostalgic memory for us.

Early Challenges in Nishijin Weaving

After graduating high school, Katsuhisa’s first challenge was learning to tie warp threads. As a left-handed weaver learning from his right-handed mother, he had to adapt techniques through observation. He also recalls the difficulties of working with paper punch cards before digital jacquard systems.

The hardest part at first was learning to tie warp threads. I’m left-handed, and my mother taught me by example, but her movements were right-handed, so it took time to adjust. Even the “nonotsugi” knot we use in weaving is reversed for left-handers.

Back then, we used paper punch cards—not USBs or floppies. When the cards tore, we had to patch them with similar paper and re-punch the holes. I didn’t know which holes meant “stop” or “color change,” and it was confusing.

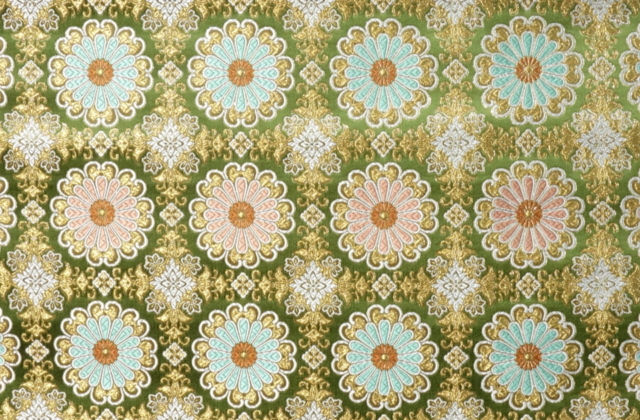

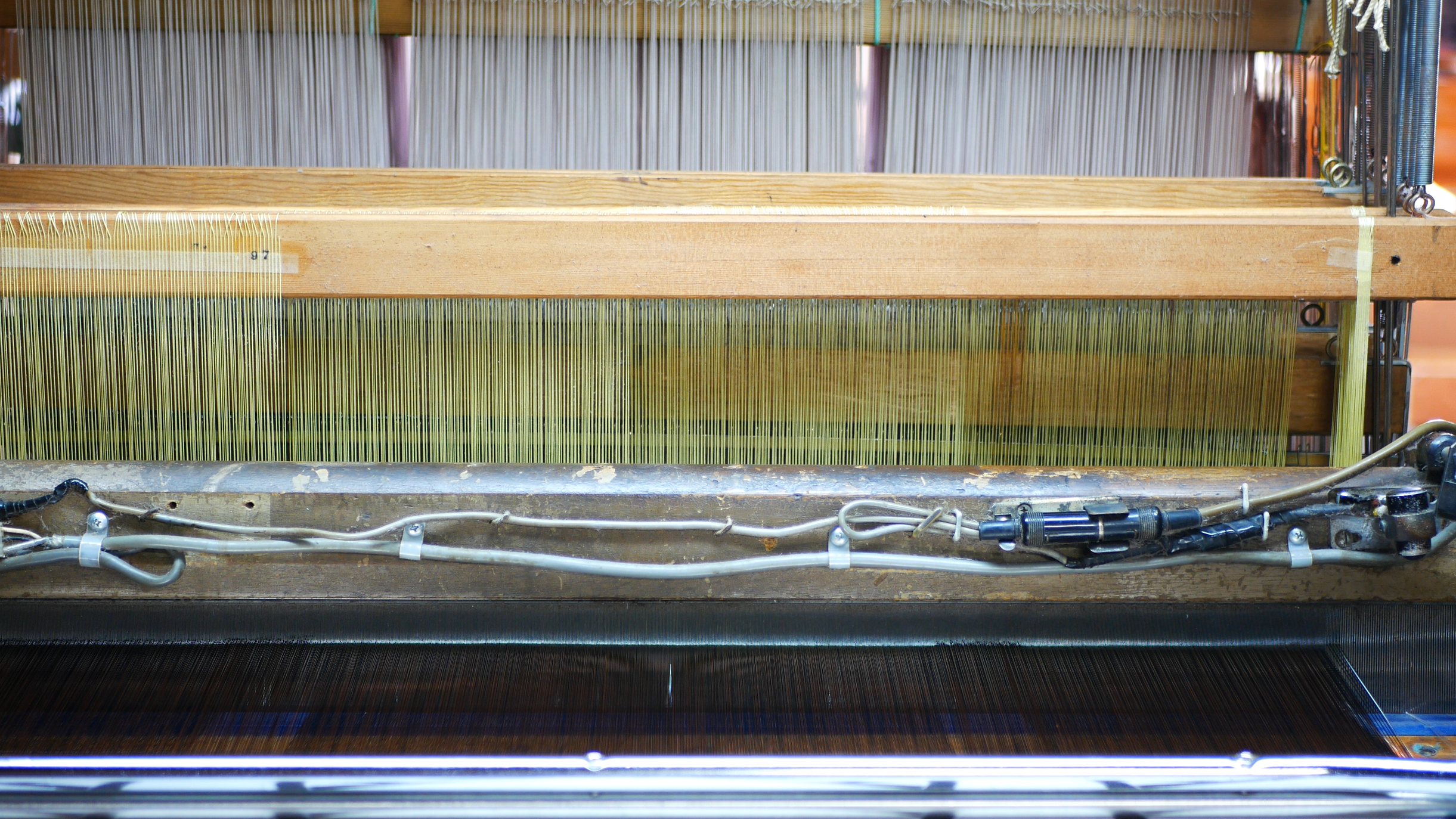

The fabrics we wove at first didn’t require color changes—we could leave the shuttle in place. But Okamoto’s textiles involve many stops and color substitutions. We use looms with 6 or 12 shuttle boxes, and sometimes more colors than boxes. You have to insert stops to switch colors correctly. When there are many substitutions, it’s extremely tense.

Photo: Socca Co., Ltd. 2017

The Challenge of “Can I Really Weave This?”

“It’s less about fun and more about the tension of getting it right,” says Katsuhisa. Since working with Okamoto Orimono, he’s come to appreciate the depth and difficulty of weaving.

Their kinran designs have become more complex over time, with many color substitutions. It’s nerve-wracking—I have to stay focused on each loom.

Back in the paper punch card days, we marked the stops and changed colors in sequence. It took a lot of concentration. Now, most of my work involves the tension of wondering, “Can I really weave this properly?”

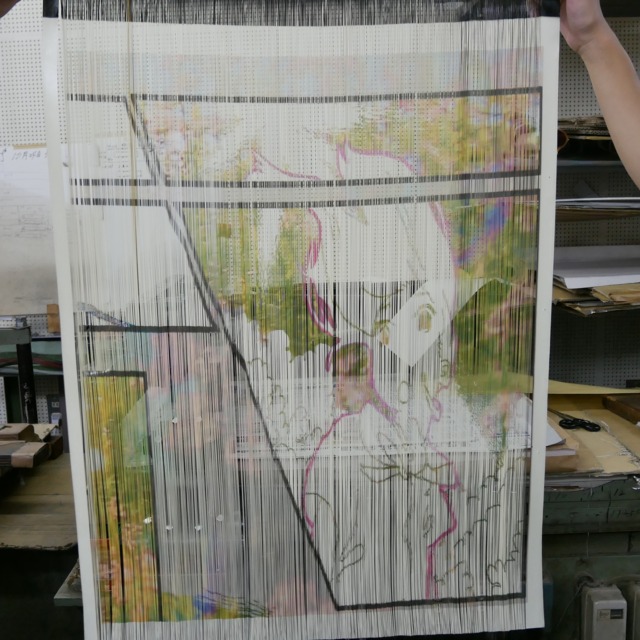

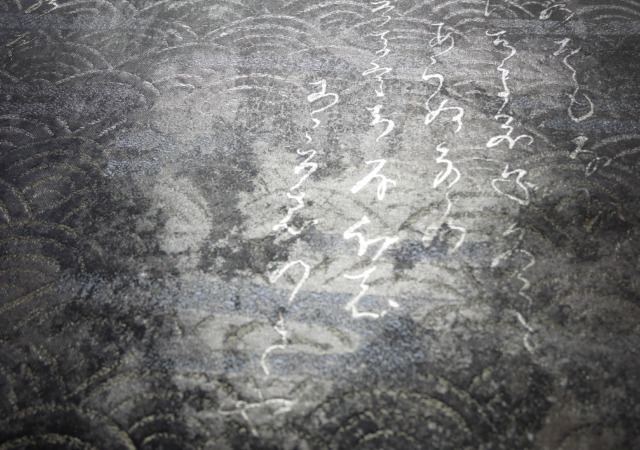

The photo below shows one such complex piece: a full silk Nishijin kinran featuring monstera leaves and birds, with many color substitutions.

A Life Woven with Family

The couple shared that having their family close and working together was the greatest joy. Being able to raise their children while weaving, and having their children understand the work, has been a source of pride and fulfillment.

A Warning for the Future – Tradition at Risk

“This work can’t be done alone. If even one person—loom repairer, thread supplier, material vendor—is missing, we can’t weave,” says Katsuhisa. He warns that without fundamental support from public institutions, the survival of traditional crafts is in jeopardy.

It takes many people—loom technicians, thread suppliers, material vendors—to complete a single textile. If even one person is missing, we can’t weave.

The lack of successors is a serious concern. We often wonder how many more years we can keep doing this.

Unless artisan wages become more attractive, it’s impossible to sustain. If you ask a university graduate to work for current rates, it’s just not viable.

This isn’t just a weaver’s problem. I believe the government must take fundamental action to preserve traditional crafts. Without their support, continuation will be extremely difficult.

(Interviewed on September 11, 2025 / Text by Ema Okamoto)

Editor’s Note

When I joined Okamoto Orimono, Nunohira-san was already one of our weavers. Back then, his parents and he worked together. We sent yarn and warping reels to Tango daily, and rolls of woven fabric arrived in bulk. I remember inspecting cloth for household Buddhist altars and thinking, “Do people really buy this much altar fabric every day?”

I create jacquard data. When I started, we had many small looms with 6 or 4 repeats across the width. Now, we use only 2-repeat or single-repeat looms. Over 30 years, much has changed. Punch cards became floppy disks, then SD cards and USB drives.

Everyone younger than our president has walked this path alongside Nunohira-san. We hope to continue weaving Nishijin together. Thank you always.

In this series, we’ve visited thread makers, dyers, warpers, foil artisans, cutters, designers, starchers, and weaver. Thanks to these artisans, our weaving work is possible.

For a full list of artisan interviews, click below: