The Cultural Role of Nishijin Ori Kinran

Historical Background

Nishijin Ori Kinran has long been cherished and developed as a luxurious textile for the elite. It is used in various contexts such as decorating shrines and temples, priests’ kesa robes, noh costumes, and hanging scrolls, embodying the essence of paradise through its silk. Kinran is extensively used in Buddhist priests’ robes and ceremonial tools, with different patterns designed for each sect. This textile, known as “Nishijin Ori Kinran,” has also been valued as a symbol of social status and authority, representing power and wealth.

The Aesthetic of Nishijin Ori Kinran

Unique Craftsmanship

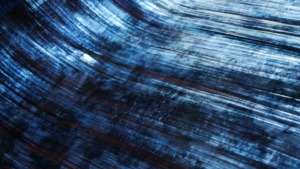

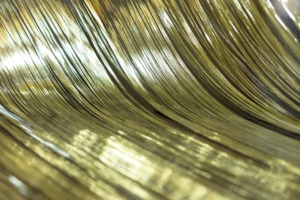

The “Hikibaku” of Nishijin Ori Kinran involves a unique production process. Specially crafted Washi paper is coated with lacquer, overlaid with genuine gold leaf (our usual genuine gold leaf is 23-karat gold from Noto), and finely slit into threads known as “Hikibaku.” This meticulous craftsmanship defines the texture of Nishijin Ori Kinran.

This video, produced by the Kyoto Gold and Silver Thread Industry Cooperative Association, explains the process of creating genuine gold threads. Please take a moment to watch it.

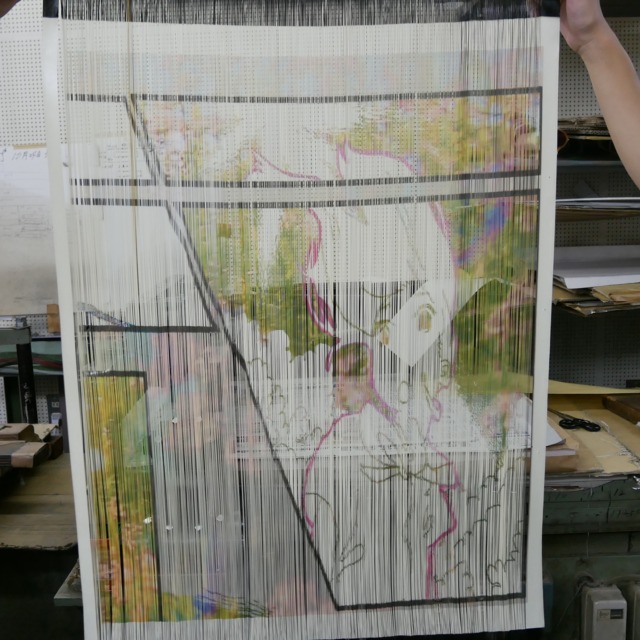

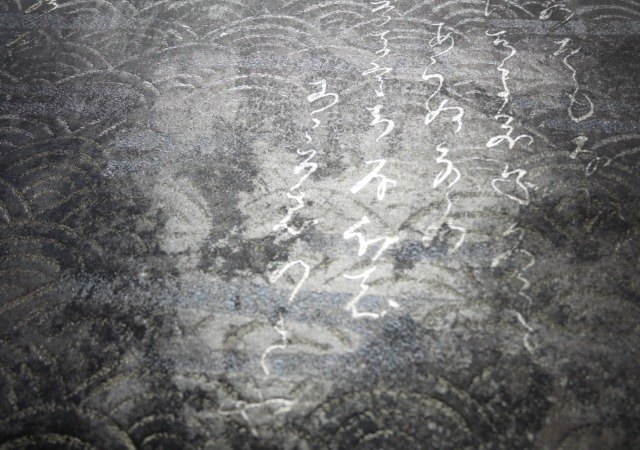

Patterned Hikibaku, with designs drawn on Washi paper, is indeed a fascinating material. It offers unique textures and visual appeal. Here’s an example of four different color patterns in Patterned Hikibaku.

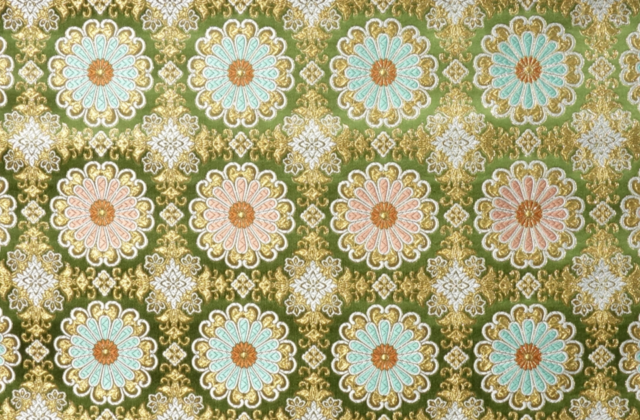

Luxurious Patterns

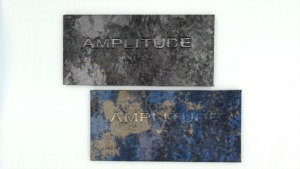

Gold threads and Hikibaku are woven together with silk threads as weft threads, creating a three-dimensional texture and radiant golden glow. This highlights the opulence of the patterns. The creation of each piece of Kinran requires the skilled hands of artisans and significant time and meticulous attention, whether hand-woven or woven on a power loom. The resulting silk textile represents the pinnacle of craftsmanship. Below are images of Jacquard fabrics that all use Patterned Hikibaku.

Aesthetic and Cultural Significance of Kinran in Japan

Junichiro Tanizaki’s “In Praise of Shadows” also depicts the allure of Kinran. Kinran holds a subtly yet crucial place in Japanese traditional culture and design. Despite its delicacy, Kinran exudes an opulent elegance, reflecting the Japanese sense of beauty.

The Golden Light in Darkness

When you step into one of those large buildings, deep into a room where no light from outside can reach, you may find golden sliding doors or folding screens glowing faintly, capturing the light from a distant garden. This reflection, weak like the twilight horizon, throws a soft golden light into the surrounding darkness. I have never seen gold appear so sorrowfully beautiful. Passing by and turning back several times, you notice the paper’s golden surface slowly gleams from different angles, like a giant changing its expression. It doesn’t flicker rapidly but gleams with a long, patient glow. Sometimes, dull reflections suddenly flare up when viewed from the side, making you wonder how such a small amount of light can be gathered in such a dark place. This made me understand why ancient people painted Buddha statues and noble rooms with gold—modern people, living in bright houses, don’t know this beauty. But the ancient people, living in dark houses, knew its practical value too, as gold acted as a reflector. They didn’t use gold leaf or dust merely for luxury but to augment light in dark interiors. Silver and other metals soon lose their luster, but gold, which maintains its shine and lights up the dark for a long time, was esteemed highly for this reason. Similarly, maki-e is designed to be appreciated in the dark, and this principle applies to textiles like gold and silver-threaded fabrics. Gold-threaded kesa worn by monks serves as a prime example. In today’s brightly lit temples, they often appear garish, but during traditional ceremonies in historical temples, the gold-threaded kesa harmonizes beautifully with the wrinkled skin of old monks and the flickering altar lights, enhancing the solemn atmosphere, as the darkness conceals most of the ornate patterns, making the gold and silver threads glint subtly.

Junichiro Tanizaki, “In Praise of Shadows”

Nishijin kinran is not merely a textile but a cultural artifact. The fusion of traditional techniques and aesthetics in Kinran continues to be appreciated and cherished in modern times.

The Future of Nishijin Ori Kinran

Nishijin Ori Kinran strives to preserve its heritage while adapting to contemporary needs. By incorporating new technologies and designs, it continues to create Kinran that connects to the future.

Nishijin Ori Kinran, as a symbol of Japanese culture, aspires to continue spreading its joyous influence as a silk textile embodying paradise. It seeks to touch the hearts of many people, bringing a piece of heaven into their lives.